Solving Tension-Related Neck & Shoulder Pain

How we can learn to fix this crippling problem

Something troubling me over the past year is the unbelievable pervasiveness of pain in the neck, upper back, and shoulders (what I will refer to in this article as NBSP). More than half of the people I work with—you—have described either chronic or acute pain in this region of the body. As a lifelong struggler of neck pain myself, I can attest to its crippling nature but also the benefits that the solutions provide.

I can also say that in the past 14 years of working one-on-one with individuals, I have only witnessed the prevalence of NBSP go up. This is an issue that needs to be addressed.

Muscular imbalance

In short, NBSP comes from an imbalance in the musculoskeletal chain. Every skeletal muscle (the muscles that support our body when we move) in the body works with other muscles to support daily movements.

Think of something basic, like walking. It may seem inconsequential; we do it every day with little thought. But how many people do you know who experience knee pain? Hip pain? Lower back pain? A poor gait can directly cause these problems. In many cases, the hamstrings and the glutes do not provide enough of a pull to help us ‘glide’ over the ground. As a result, we end up with a more flat-footed ‘clomping’ gait. This, in turn, puts far more pressure on joints like the knees, hips, and lower back.

The same principle applies to the shoulder girdle, which are the bones that float over your rib cage and allow for mobility of the arm and shoulder, which is a focal point of NBSP.

How does this imbalance cause NBSP?

Most causes of NBSP are lifestyle-based. There are many exceptions, which I won’t go into much because there are people far more qualified to discuss them than me. Some of them include structural issues such as scoliosis (lateral curvature and/or rotation of the spine) and kyphosis (forward curve of the upper thoracic spine), both of which I am afflicted by. Impact trauma, whiplash or other acute injuries, herniated discs, and degenerative conditions can also cause NBSP.

As for lifestyle-based factors, you can guess the culprits: We sit too damn much, we stare at screens too damn much, and we are too damned stressed. We know these things. But what is actually happening to our body?

If you’ve ever been in a situation where you have a colleague who neglects a big portion of their job, forcing you to do both your work and theirs, this is very similar to how the muscular chains in our body operate with poor posture.

Here are a series of bullet points of what happens to our upper body when we sit too much:

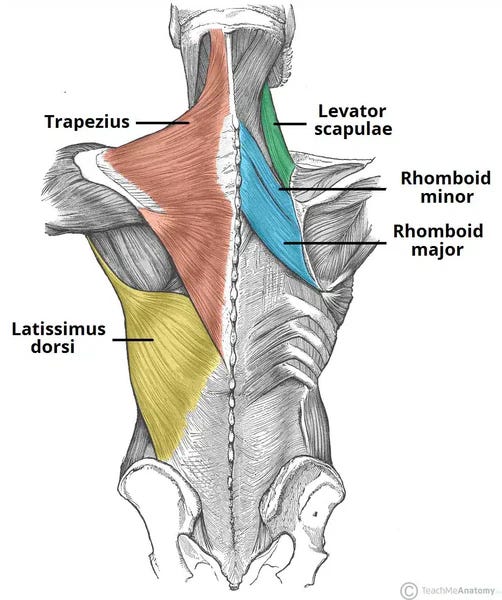

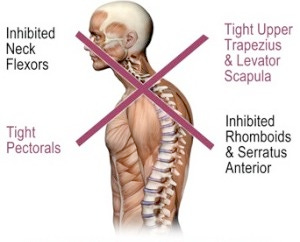

1. Our head lurches forward. Gravity pulls straight down regardless. Every inch the head lurches forward from its neutral position adds an additional 10-12 pounds of downward force on the neck—imagine putting a 20lb weight on your head and carrying it around! This puts tremendous strain on three of the primary muscles that support your neck: Upper Trapezius, Levator Scapulae, and Scalenes.

When a muscle is stressed, do we want that muscle to be contracted or lengthened? We want both—a balancing act; we want that muscle to be elastic. But with our head lurched forward, we are only applying a stretching force on those 3 muscles. What’s going to happen?

The Upper Trapezius and Scalenes will become overstretched and lose their ability to shorten. In other words, the muscles will weaken. But they also have the important role of holding our head up. You can see the dilemma.

The Levator Scapula is trickier. It originates on the cervical spine and inserts on the scapula, which floats in our body. As lengthening force is applied, it will actually pull our shoulder blades up! Now we have serious problems with our shoulders and middle back because there are other muscles, like the lats, that are attached to the scapula. These muscles now have excessive tension placed on them, so they will lengthen and weaken.

Lastly, the muscles that flex our neck (pull our chin to our chest), our Sternocleidomastoids, get stuck in a shortened, tightened position—much like our hip flexors from prolonged sitting. This exacerbates the tightness of our neck by pulling harder on the other three aforementioned muscles.

2. Our shoulders and upper back round forward. While you’re reading this, observe how you are sitting. What are your shoulders doing? A common cause of NBSP is that the shoulders round forward, creating a significant imbalance in our upper body muscles.

The shoulder is comprised of two joints: The acromioclavicular (AC) joint and the glenohumeral (GH) joint.

The acromioclavicular joint is where the clavicle meets the acromion (the upper, outer-most edge of our scapula). You can find it by tracing your clavicle to the shoulder and feeling the bony point at the top of your shoulder.

The glenohumeral joint is where the humerus's (our upper-arm bone) upper head meets the “socket” of our scapula, called the glenoid cavity.

The GH joint is primarily what we’ll be focusing on since this joint is one of the joints in the body that degenerates the quickest from the frequency of use, combined with lifestyle factors. When our shoulders round forward, this is typically the joint that suffers the most. How?

There are three key muscles that are severely impaired when the GH joint rolls forward, especially in tandem with the head and neck lurching forward: The lats, middle traps, and rhomboids. Each of these muscles will get stuck in a lengthened, weakened position.

As you’ll read below, these three muscles are essential for maintaining good posture and preventing NBSP.

Lastly, three major chest muscles—pec major, pec minor, and serratus anterior—each shorten. Much like the hip flexors and sternocleidomastoids, they lose their elasticity. But what’s more problematic is that these shortened muscles then pull on the GH and AC joints, amplifying the stress on the neck and back muscles.

How can we solve NBSP?

There is power in knowledge. Knowing what is precisely happening to our body can help us channel our focus and our training. The first thing I try to impart to everyone I work with is to develop neuromuscular control—the ability to contract a muscle with your mind. It takes time, patience, and focus. But eventually, like I mentioned last week, you chip away enough, and suddenly, you can feel your glutes pulling you forward when you walk or your lats pulling your shoulders back. Before long, it becomes automated, as I discussed in Automated Processes.

To solve NBSP, we need to develop the awareness and control of the muscles needed to stabilize our posture.

When discussing lower back pain, there’s a term called “dead-butt syndrome”. In short, when we sit too much, the glutes don’t do anything, so they become dormant. This cascades into more problems that physically alter the angle of the pelvis, which in turn puts an enormous workload on the lower back muscles, which are not built to handle that amount of stress.

The upper body does something similar, and I would like to coin a new term: “Dead-lat syndrome”. (I would like to call it dead-LRT syndrome because technically it’s the lats, rhomboids, and traps that all go dormant. But it’s not as catchy. Anyway, I digress.)

The lats, rhomboids, and traps all work to stabilize the scapulae, shoulders, and spine, remaining in their neutral positions. Here is an exercise you can do on your own to engage all three. You can do it anytime, anywhere, and as often as you like:

Step 1: Simultaneously do the following three things: Inhale deeply, expand your chest, and roll your shoulders back. Feel your chest pulling away from your sternum in the middle of your chest. Observe how this will pull your chin upward and straighten your spine.

Step 2: While holding this position, attempt to contract the LRT muscles: Lats, rhomboids, and traps. It may be impossible at first, but that is perfectly okay. This is yet another reason why strength training is invaluable. If you can feel them, observe what they do to your scapulae; notice how they hold your shoulders back; feel how they align your cervical spine (neck) with your thoracic spine (middle and upper back).

Step 3: Exhale slowly and let your shoulders sink. However, attempt to keep your chest expanded. In strengthening our back muscles, it’s crucial we not let the chest collapse into its shortened position. The back muscles need to remain engaged and not be allowed to lengthen.

Each repetition should take you about six to eight seconds, and I recommend performing about three to five reps at a time.

Conclusion

This is not the solution for NBSP, but it’s a hell of a good start. I routinely perform this step-by-step process and many of you reading this are familiar with it from your time working with me. This process will help you build neuromuscular awareness of what good posture should feel like.

The muscles mentioned in this article need to be strengthened and become more elastic. It takes time. If you suffer from NBSP or any form of muscular pain, be patient with yourself. Again, as we focused on last week, chip away a little bit at a time. When you look back, you may just be amazed.

Other Learning

Podcasts:

Articles:

I Should Have Been Braver — Ruxandra Teslo

Make-Work is not the Future of Work — Noah Smith

High-Intensity Interval Training and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: Promising but Limited Findings — Peter Attia, M.D.

The Biggest Man-Made Disaster Ever? — Kyla Scanlon

The Mr. Beast Memo is a Guide to the Gen Z Workforce — Kyla Scanlon